WRITING

22 Trauma Seasons

Kathryn Ko, MD, MFA, FAANS

In the streets of New York,Dope

fiends are leaning for morphine The

TV screen followed the homicide scenes You

live here, you’re taking a chance

So look and I take one glance, there’s a man inside an ambulance

Look behind you when you walk

That’s how it is in the streets of New York —

“ Streets of New York” by Kool G. Rap and DJ Polo, 1990

August 1991: 2 a.m. I am driving to the hospital to do a craniotomy. I am not thinking about surgery. My mind is preoccupied with getting there. Because of a mistaken short cut, I am completely lost. I end up on a deserted street with burned-out buildings and vandalized abandoned cars. It is scary quiet. The streetlamps are shards, the pay phone is cracked, and I shouldn’t be here. I am disoriented. My hands shake as I unfold a map and strain to read the graffiti- disfigured signs. Headlights appear in the rearview mirror. A sedan with tinted windows is coming. I’m no longer in normal sinus rhythm. I continue down the street and stop at the red light. The sedan pulls close to the side of my car. They can see me, but I can’t see them. I inch my car forward. The sedan follows. The red light is endless. I panic and stomp on the accelerator. The sedan gives chase. I am scouring the streets for something, anything familiar. And there it is: Dunkin’ Donuts. Open 24 Hours in lifesaving neon. I pull in. The clerk knows that look on my face. He bolts the entry door. I lay my map on the counter. He marks the way. I arrive at the hospital and nearly hug the circulating nurse.

There are 15 Level One trauma centers serving the five boroughs of New York. Manhattan has four; the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens have three each; and Staten Island has two. During my more than two decades of practicing in the city, I have worked at seven trauma centers in every borough except Staten Island. I also have attended neurosurgery clinics in several non-trauma facilities.

The New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation provides a significant proportion of the care in these hospitals, including my current posting at Harlem Hospital. Although each has a slightly different mandate, the unifying element of my experience is that each is located in an impoverished and high-crime neighborhood. Excluding Bellevue Hospital, which is affiliated with New York University and Elmhurst Hospital Center (a Mount Sinai Hospital affiliate), the other “city” hospitals have no neurosurgery residents. They rely on either general surgery staff or other midlevel practitioners for in-house support. Over the years, some of the areas have changed or gentrified, and the hospitals often evolved with their neighborhoods.

Craniotomy in G Sharp (Acrylic on canvas) by Kathryn Ko

Craniotomy in G Sharp (Acrylic on canvas) by Kathryn Ko There is a seasonal cadence to the work. Memorial Day through Labor Day is considered the summer “trauma season.” It is heavy with neurosurgical emergencies. Trauma season means that weekends and nights likely will be spent in the operating room managing a variety of cases that encompass the total spectrum of human violence. We expect to encounter injuries from bike or car accidents, gunshot wounds, blunt trauma and spinal trauma. These are in addition to the daytime elective operations. It makes for full volume, around-the clock surgery. The cooler temperatures bring a reprieve from trauma season. A more relaxed tempo pervades the winter months as more elective cases fill the operating schedule. My case mix tends to reflect the seasons.

Many of these hospitals lack the latest technology. I often have to use an older generation tool or instrument. The case can be completed smoothly, but operating under these resource constraints is less convenient. Limitations are overcome with extra work and middle-of-the-night problem solving. It is rare to be assisted by a dedicated neuro-trained team. Learning to trouble shoot and have several plans is mandatory. Working with limited resources has taught me to be flexible. When necessary, I discard traditional solutions in favor of what is possible at that particular facility.

My art background, which illuminates an entirely different perspective, has helped me envision apathy through some of these obstacles. Setbacks become an invitation to switch thinking from neurosurgeon to artist to find a potential remedy. For example, I observed at one hospital that a properly pressurized pneumatic cranial drill emits noise in the key of G sharp. A half note above or below will result in the malfunction of this particular instrument. An audible test prior to the incision alerted us to a potential problem.

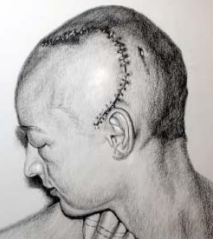

Danger Trumpet Man (Charcoal on paper) by Kathryn Ko

Painting improves my ability to conceptualize in three dimensions. It decreases my dependence on neuro navigation and is a valuable asset when this technology is not accessible. Other neurosurgical colleagues have their own unique strategies, and I have drawn strength from their persistence and passion.

Our patients speak every language, from Albanian to Urdu. They come from not only New York’s minority and socially/economically challenged populations, but also West Africa, Mexico, Central and South America, Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia. Translating services are, therefore, in heavy demand, and speaking Spanish is definitely a timesaver.

Self Portrait (Acrylic on canvas) by Kathryn Ko

Self Portrait (Acrylic on canvas) by Kathryn Ko Many of the patients have lives I cannot comprehend. A survey we conducted in 2010 revealed that fewer than one percent of patients visiting a neurosurgery clinic in the Bronx had a computer or Internet access. In another instance, I was confounded by my consistently high length of stays for elective spine surgeries. No matter what, the patients refused discharge. We finally understood that for these patients, staying in the hospital was preferable to going home or to no home. We were uneasy with discharging homeless patients. Many would simply disappear, with no phone, no contact, no way to follow up, staples intact. We worried about what happened to them. Telegrams were returned unopened. I often questioned if these patients understood what they had gone through. If they did, only a minority ever said so. It is paradoxical that you can save someone from dying, but hardly touch the rest of their life. A line from the poem “Four Quartets” by T.S. Eliot consoles, “For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.”

Commercial or private insurance is a rarity in my practice. Had it not been for stipends from the hospitals, I don’t suppose any of us could continue. I am grateful to the army of medical professionals who through the years teamed with me and buoyed me through the difficult periods. And surely, without art, I may have succumbed to burn out and retreated to a different practice. Painting provided a place to put these experiences and capture the truly authentic lessons that are dismissed in the stress of a hectic hospital day or decade. Coupling my neurosurgical career with my art saved me.

January 2013: Midnight. I pack technology. I have a Droid, and my car has a GPS. I’m driving north through Harlem. I cannot get lost. Truth be known, I still grumble about the late night dash to the hospital. But these days, it is softer and toned down by my affection for this place. After the operation, I pass my favorite Dunkin’ Donuts — for me, a sentimental symbol of security. Always open just in case. This dawn, I stop in. The overnight manager knows that look.

“Hard night, doc?” she asks.

“No,” I say, “not hard. Not at all.”

The Incredible Lightness of Breathing

Kathryn Ko, M.D., MFA

In cruel April2 this brain surgeon has become an airhead.3 I have neglected to write my essay. The epidemic has rattled my brains like an empty oxygen cannister clattering on the ICU floor. I am gasping for palliative signs as I struggled to write a sentence for my assignment. The shakes that wake me are not COVID, they were caused by the dread of my approaching deadline. Lockdown is a pathetic alibi.

COVID-19 is a dire metaphor for all that unites us and all that divides us.4-5 Wearing my mask and gloves, wielding a Clorox wipe instead of a scalpel, I don’t recognize myself anymore. The armored up pedestrian on the street looks more like a surgeon, than this surgeon. I beg for a breather while brooding over the invisible viruses, seeing them everywhere. This virus is carbon monoxide and all we can do is cover our faces. When we are rebreathing our own breaths, breath has become air.6

My creativity was further diminished by the death of James Goodrich7, a gentleman if ever I cut with. Although renown as a world class neurosurgeon, he was more historian than surgeon. To him contemporary neurosurgery and its history are inseparable twins, safest in his hands. Years ago, he gave me a wooden Polynesian statue from his collection of antiquities. Its dilated pupils spooked me. Fearing bad luck, I gave the wood relic a quiet exit to storage. There “he” remained for 20 years with his eyes turned to the wall. After Dr. Goodrich’s passing, I positioned the piece on my nightstand, in audience to his memory.8 Edgy under its glare, the less I sleep.9 I suspect that heaven is too small a place for someone like Jim. I choke and don’t complete my journal task. His death is a cruel excuse.

Surgeons are optimists, even with terrible trauma; otherwise we would never make the first cut. We know that wounds heal. The fortune-tellers predict that the world might be better after COVID, but surgeons do not wait for a crisis to improve. We seek “ better “ even after a perfect operation. When the world is well, we will respect the mysterious exchange of gases that keeps us alive, but we will also fear inhaling because now we know it can kill us. If we want things to remain the same, we will have to change the way we breathe.10 We shouldn’t have to stop breathing to be better.

The artist side of my brain is imagining what a COVID-19 healthcare monument will look like. Perhaps we can memorialize in one tribute all the infectious risks from air to blood that healthcare professionals have endured. A few diseases ago, I remember standing at the scrub sink with Dr. Goodrich preparing for emergency surgery on a patient infected with blood-borne virus. I was scared, thinking: What if a needle with infected blood pierces my skin? What if I get the virus? The risk was breathtaking because there was no antidote, no medication, no cure – we had only our skill and luck. Still, we stayed put. That’s what healthcare professionals do every day and it’s gratifying that the profession is finally getting a well-earned salute for that commitment.

These days the wooden figurine is my confinement companion, changing the air with its Ha (Hawaiian for breath).11 Its odd staring eyes have stirred me. I am reminded that art and science are conjoined twins with their own approaches to the sick. I inhale the wood smell and feel the free-flowing air of the Pacific. An object that once had an aura of ill wind is, on this April night, a touchable remembrance of an esteemed colleague. I take a deep breath and knock wood anticipating a flow of inspiration.

What an unbearable alibi breathing is.

A Neurosurgeon’s Lockdown Reading List

1. The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Milan Kundera, 1984

2. The Waste Land

T.S. Elliot 1922

3. When the Air Hits Your Brain

Dr. Frank Vertosick, 1996

4. Death by Water

Kenzaburo Oe, 2009

5. Illness as Metaphor

Susan Sontag, 1978

6. When Breath Becomes Air

Paul Kalanithi, 2016

7. Pediatric Neurosurgery

James Tait Goodrich, 2008

8. Memoirs of Hadrian

Marguerite Yourcenar

9. The Less you know the Sounder You Sleep

Juliet Butler, 2017

10. The Leopard

Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, 1958

11. Hana Hou

Vol 23 #2, May 2020